Picture this: You’ve got a perfect excuse to go shopping. You’re on the hunt for the perfect … something.

Maybe you need a new pair of shoes, or a relaxing getaway, or a gift for your newborn nephew.

Whatever it is, you’re getting more and more excited looking and hunting — and then finally, you find it. That perfect something you absolutely cannot walk away from. While the cost exceeds your personal budget, it’s what you were hoping for. Purchase made, mission accomplished … right?

Later, your feelings begin to change. You’re definitely not excited about your purchase anymore, or even happy. You’re starting to feel anxious about the cost.

That’s the emotional roller coaster of shopping: For every dollar we spend, there can be an emotional cost, too. Many people experience this. It’s not just you, it’s science.

Researchers have studied the “shopping high,” discovering observable effects on our brains and bodies when we shop. Your body and brain are on that spending roller coaster with you, and on the crash afterward.

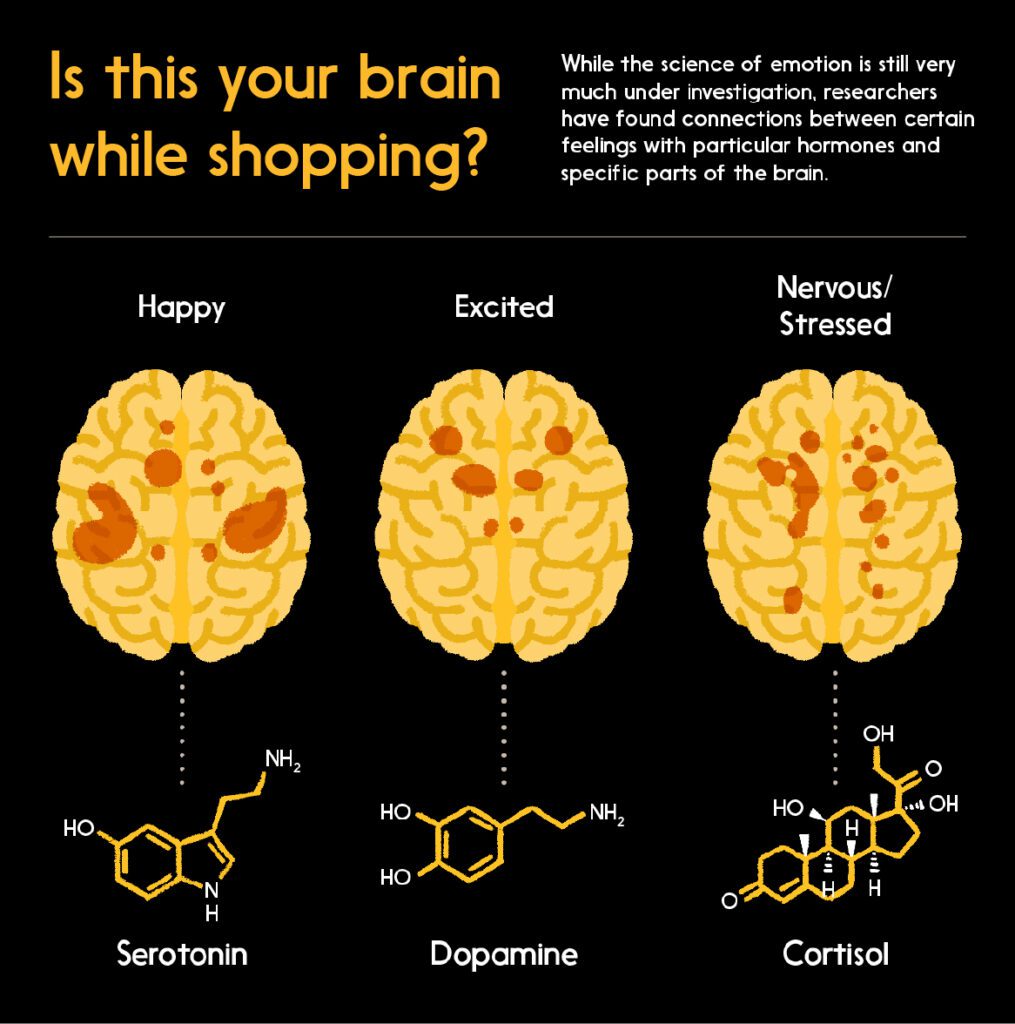

Take hormones, for example. Scientists have explored the connection between the hormone dopamine and shopping. Dopamine is associated with excitement; it helps us experience the thrill of the hunt, keeping us motivated while we track down the perfect birthday gift for a hard-to-buy-for friend. A rush of dopamine feels great, but there’s a catch: The brain releases it in anticipation of a reward (say, a purchase), as opposed to the reward itself. That could be why the “shopping high” vanishes once the spending is done.

Serotonin is associated not only with returning to a state of contentment when it’s disrupted, but also with generosity and other positive, “prosocial behaviours.” It could help explain warm feelings about buying a gift after you’ve given it away. Meanwhile, cortisol, sometimes referred to as the “stress hormone,” appears to play a part in regretful feelings like guilt and shame — and, potentially, buyer’s remorse.

Using imaging technologies, researchers are also uncovering connections between particular parts of the brain and certain emotions — ones that we experience while we shop. The graph below shows parts of the brain that activated — that is, experienced increased blood flow — in response to different emotional stimuli, based on functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

The question then becomes: Is there a way to spend money that delivers the excitement of shopping and the happiness of a sound purchase, while avoiding the nervous, anxious feeling of a “bad” purchase? Can we engage in mindful spending in a way that maintains our bodies (and personal budget plans) in balance, and keeps the roller coaster from crashing too hard?

The Interac behavioural science experiment

At Interac, we know Canadians are shifting their spending in order to lift their moods, but also want to stay on a personal budget and avoid debt. So we’ve just released new research into the rush of emotional responses that people have when they spend money in the hope of bringing some science to the art of smart shopping and mindful spending.

The Interac behavioural science experiment invited 1,088 Canadians to report their emotional reactions to a number of purchases big and small; ones that took place in real life and in a simulated shop. Now, in the interests of science (or at least mindful spending), let’s unpack some key results

Happiness, financial independence and sticking to your personal budget

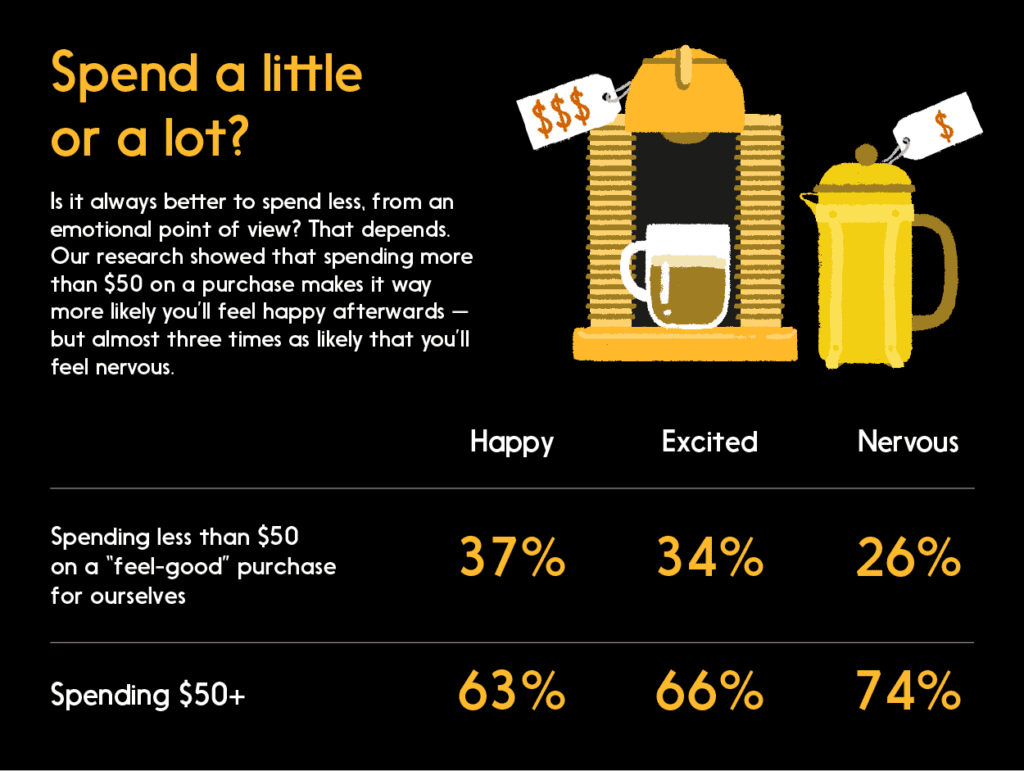

One of the more surprising results? Based on the experiences of our test subjects, a large purchase can often leave you happier than a smaller one. While it’s true that spending above $50 on a purchase gave our volunteers more nervous feelings, their reported happiness and excitement were much higher, which could be an acceptable tradeoff.

How can spending more money actually make us happier? For expert insight into the data, we’ve enlisted the help of Dr. Gillian Mandich, a London, Ontario-based happiness researcher and founder of the International Happiness Institute of Health Science Research.

Dr. Mandich suggests that autonomy — a sense of financial independence through staying on budget — could be the decisive factor in our emotional response to spending on many purchases, not simply the dollar figure.

“What we see from the research is that autonomy is more of a predictor of our happiness than how good looking we are, how popular we are or how much money we have,” she says. “When we’re spending our money, it can be a very empowering experience when we do it intentionally and deliberately.”

For that reason, staying on a personal budget with a mindful big purchase, using money you have, can be more happiness-inducing.. “When you’re paying with debit, you’re using money you already have,” Dr. Mandich notes

The greatest gift of all — may be for yourself

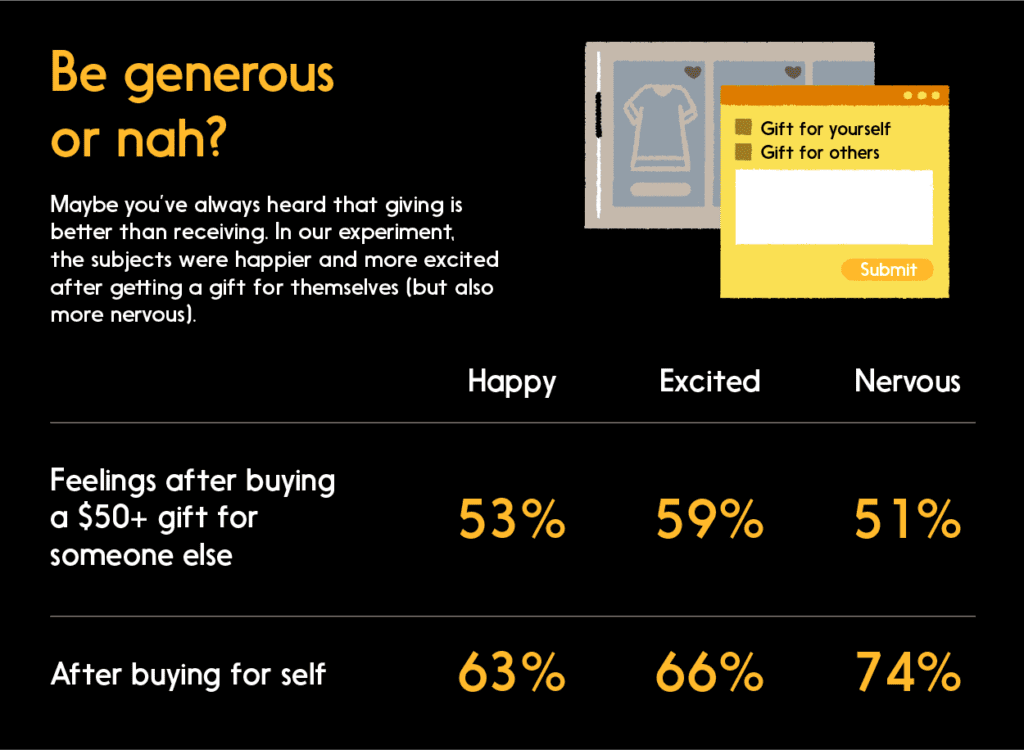

Why give? Once again, generosity is associated with serotonin, which can help us cultivate a sense of well-being. Note, however, that based on our experimental data, the ideal giftee may actually be yourself.

“Sometimes a lot of the joy of giving a gift is associated with the happiness that we see it brings to somebody else,” says Dr. Mandich.

Meanwhile, treating ourselves feels good, too.

Good times are a great investment

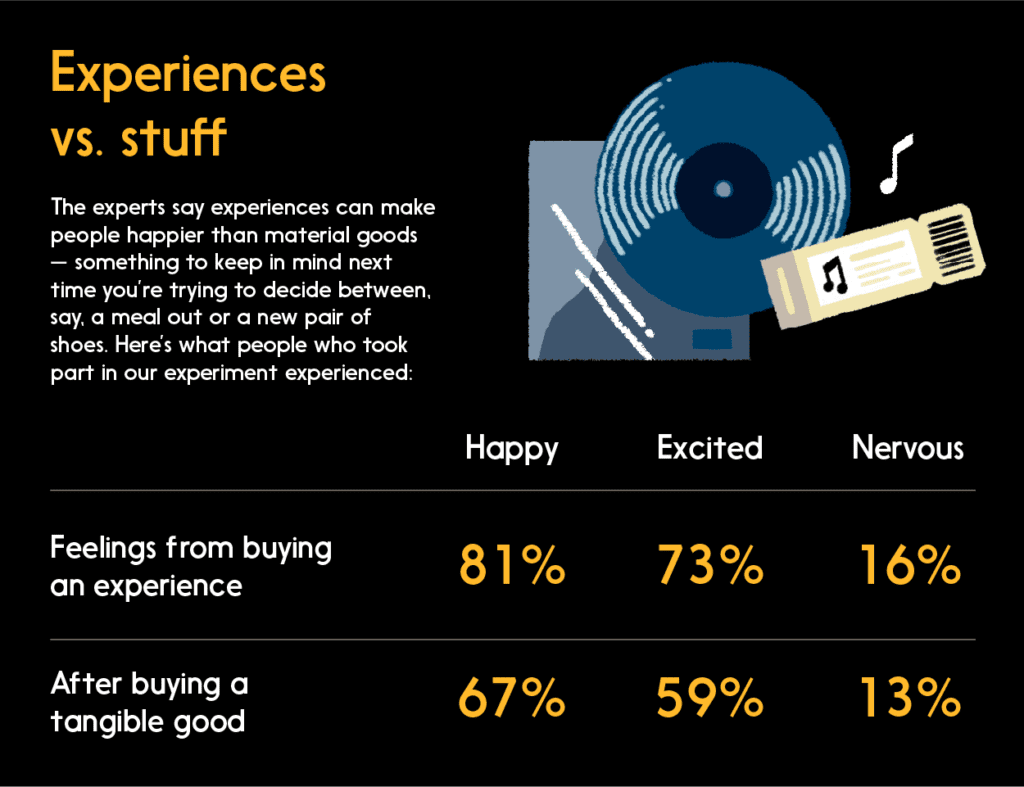

Our experiment confirmed the old nugget about experiences bringing us more happiness than stuff.

At the same time, Dr. Mandich says experiences can be modest (the results of mindful spending, for example) and still contribute to our happiness.

“It’s very clear that we can create experiences that bring us more happiness,” Dr. Mandich says, and a yoga class or an inexpensive outing could be enough. “We think it’s the big shiny moments, the graduations, the birthdays, the trips that are the things that really bring us the most happiness. But in reality, it’s really the small things day to day that add up to bursts of joy that actually make us happier.

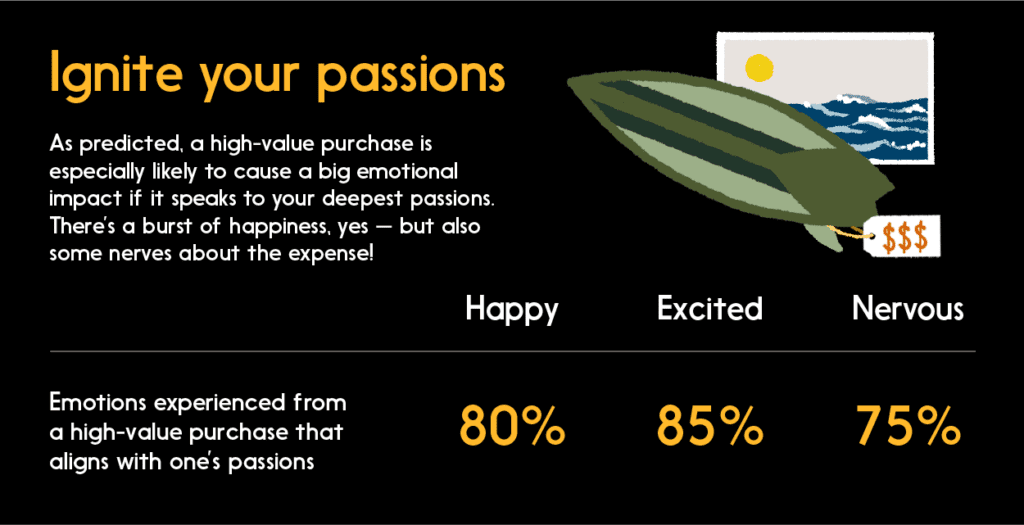

For maximum happiness, align your personal budget to your passions

Arguably the most important finding of the Interac behavioural science experiment is the insight that spending money in ways that align to their personal passions and financial independence is highly likely to induce happiness when we look back on the purchase.

“We have seen Canadians really lean into their passions, discovering new interests and activities that light them up and bring joy,” Dr. Mandich says. “When we can have the awareness to know what we’re passionate about, and then align our spending in service of that, it’s sort of the secret sauce for spending our money in a way that creates happiness.”

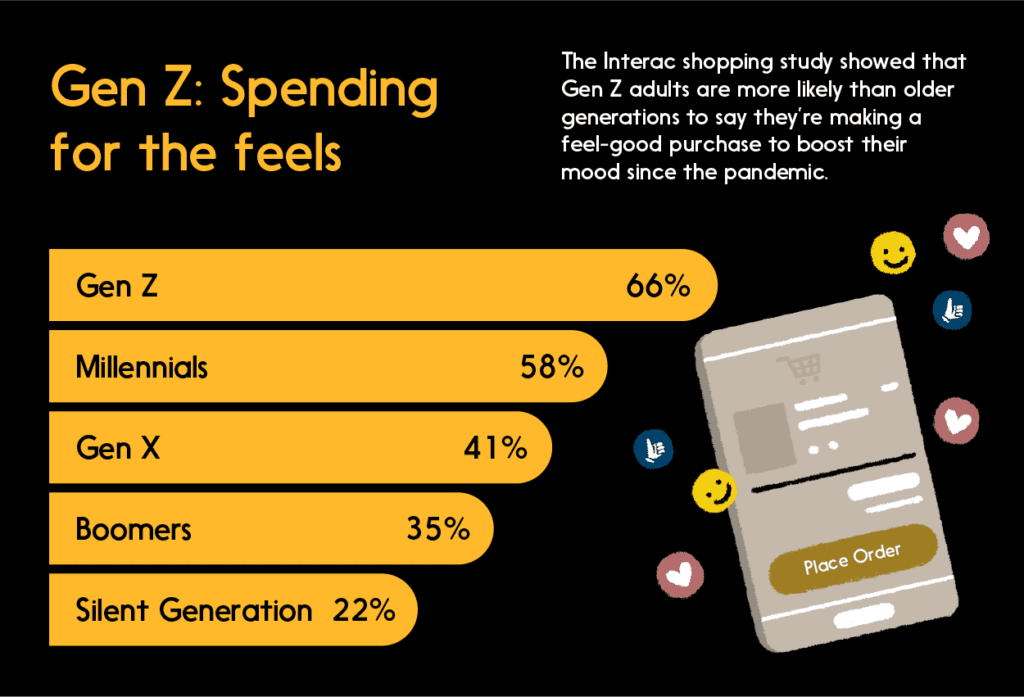

Our experiment also suggests that you’re more likely to make purchases that align with your passions if you’re younger.

Whatever your age, the lesson here is that money can’t buy you happiness — well, not directly. But discretionary spendingcan light up that brain and fire up the hormones, buying you a lasting dose of the good feels, if you align your purchases with your passions, maintain a feeling of financial independence and take charge by spending with debit.

Ultimately, it’s all about your personal budget fuelling your personal passions. “What makes us happy varies from person to person and generally lines up with our own individual passions,” Dr. Mandich says, “We have to figure it out for ourselves.”